Recent tests run by scientists from the University of California, Berkeley show that toxins released by cigarette smoke can pose a danger when they linger on clothing and furniture, BBC News reported Feb. 9.

The Berkeley researchers report having found “substantial levels” of dangerous toxins called tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) on surfaces that were exposed to “high but reasonable” amounts of pollutant.

Pioneers of the study have labelled the residue of cigarette toxins on clothing and furniture “third-hand smoke” and have suggested banning smoking inside homes and cars.

Simon Clark, director of a smokers’ lobby group called Forest, said publicizing the new results only generates alarm and that “scientists and campaigners should resist the urge to tell us how to live our lives.”

Public awareness of the Berkeley study’s results and circulation of the term “third-hand smoke” will likely increase the culture of fear surrounding smoking. But the fact that nicotine clings to smokers’ clothing and furniture is nothing we haven’t heard or smelled before.

Assigning the label “third-hand smoke” makes the study’s results jump off the page and incite more fear than if the nicotine residue were to be discussed using less charged terminology. But without the sense of urgency that comes with the term “third-hand smoke,” it’s unlikely these important research results would garner the same level of discussion.

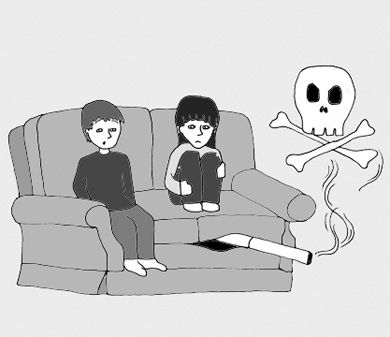

It’s a personal choice whether or not to smoke, but people have less of a choice when it comes to being around cigarette smoke. The study’s results bring to light what has been common sense for some time: when sharing a home with children or other individuals who choose not to smoke, it’s respectful to keep the nicotine outside.

There’s nothing amiss with scientists trying to influence our health choices through their research. In the past, much good has come of health research initiatives. Many positive strides have been made in anti-smoking legislation, including the ban on smoking inside bars and restaurants.

It would be hasty to accept the Berkeley study as cause to introduce legislation against smoking in one’s own home. But it’s unlikely something this drastic would come about.

It’s valid to know the effects of something so prevalent in public life as smoking, and conducting research never hurts. When it comes to health risks, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

All final editorial decisions are made by the Editor(s)-in-Chief and/or the Managing Editor. Authors should not be contacted, targeted, or harassed under any circumstances. If you have any grievances with this article, please direct your comments to journal_editors@ams.queensu.ca.