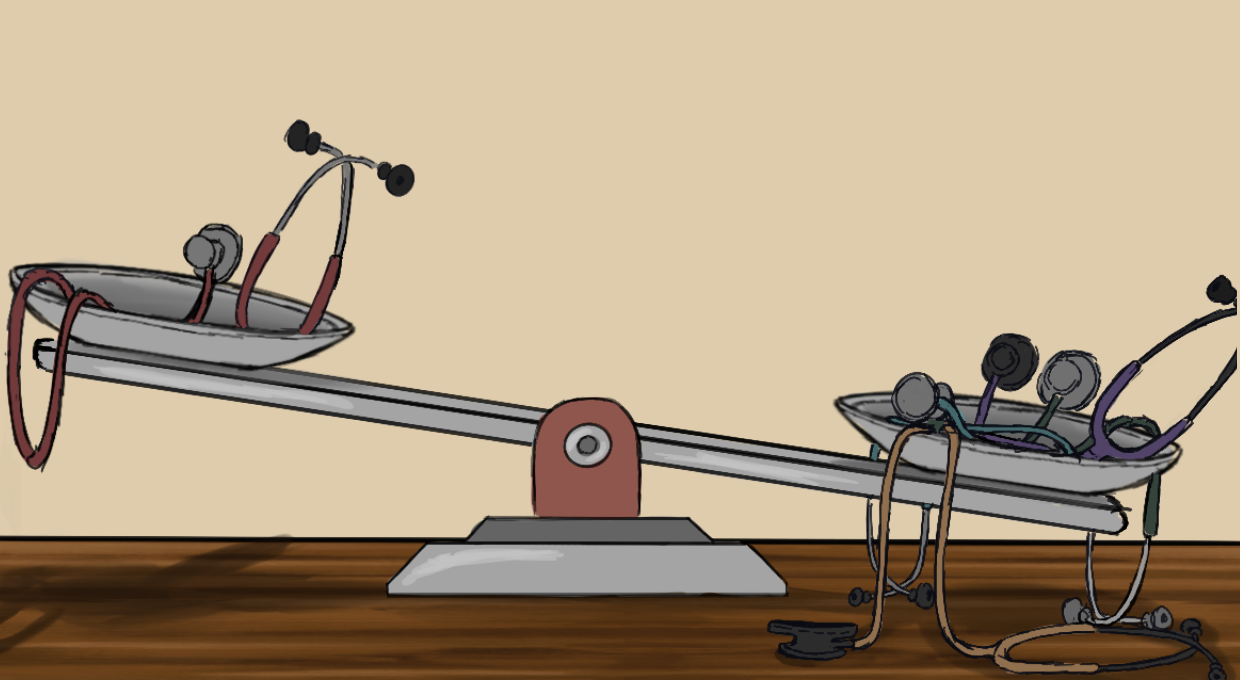

Issues with the distribution of healthcare in Canada is no secret—in 2020, only eight per cent of the country’s 92,173 practicing physicians were serving rural communities. Although medical schools aren’t the sole root of the problem, they have the potential to influence the priorities of new graduates to ease this misbalance.

A recent opinion published in The Globe and Mail alleges Canadian medical schools are more focused on promoting the research aspects of the profession instead of training their students across the range of topics in front-line medicine. Students, the authors suggest, become attracted to research positions for their status, pay, and respect in teaching hospitals.

Although this may be true, schooling doesn’t fully account for the unequal dispersion of physicians across the map.

The urban-centered distribution isn’t just a reflection of the medical schools’ shortcomings—it’s better described as a reflection of what their students do with the resources they’re given.

New graduates could be financially driven to urban areas to pay off their student debt faster, for example. In cases like these, graduates’ alma maters aren’t responsible for the personal reasons driving doctors towards lucrative urban work.

However, medical schools are still responsible for shaping the education of prospective doctors and for influencing the priorities of those entering healthcare. They also have power over who is allowed to study medicine in the first place.

The current admission process into medicine is complicated and largely flawed. A science-based curriculum, the highest marks, and extensive research experience are treated like the only acceptable criteria for success—and it attracts a certain type of person to medicine.

Eligibility falls to those who feel a natural expectation to overachieve and are less likely to move to an isolated community, away from ground-breaking technology and diverse options.

As a result, Canada’s medical schools filter for a specific, cookie-cutter group of people and exclude many who genuinely want to help future patients but don’t fit the mold. The focus rests on privilege and prestige rather than earnest dedication.

Admissions committees should focus on assessing the clinical aptitude, ethics, and critical thinking skills of applicants. Medical schools in urban areas could focus on building satellite campuses in poorer and more rural communities, fostering compassion and care for those often overlooked by the healthcare system.

The Canadian government could pitch in as well. For example, forgiving part or the entirety of student debt for new physicians in rural areas could be a meaningful incentive for doctors to spread their practices outside of urban centres.

Additionally, financial and educational resources should be provided for those who didn’t get into medical school on their first try and want another chance. An accessible admissions process fosters motivation and avoids pushing away committed applicants.

Being a doctor isn’t just an upper-class discipline—it’s a moral obligation to help patients, regardless of where they live. It’s time medical schools foster humanity in their students, not the desire for thick wallets.

—Journal Editorial Board

Tags

healthcare distribution, medical school

All final editorial decisions are made by the Editor(s)-in-Chief and/or the Managing Editor. Authors should not be contacted, targeted, or harassed under any circumstances. If you have any grievances with this article, please direct your comments to journal_editors@ams.queensu.ca.